(originally presented on BBC Radio 3 – The Essay/Something I Have Never Talked About Before)

I am thinking about Arundhati Roy’s novel – The God of Small Things – about that moment when the title first takes on a certain resonance. She writes:

And the air was full of Thoughts and Things to Say. But at times like these, only the Small Things are ever said. Big Things lurk unsaid inside.

I am thinking about that as I sit down to write this thing, as I think through this question you have asked me – something I’ve never really talked about before.

I am thinking as well about another writer, The Trinidadian/Canadian poet and essayist, Dionne Brand. She is addressing an audience in Toronto, and she begins her speech in a powerfully daring and honest way. She says: Some part of this text we are about to make is already written…for that I am a black woman speaking to a largely white audience is a major construction of the text. Blackness and ‘whiteness’ structure and mediate our interchanges – verbal, physical, sensual, political – they mediate them so that there are some things that I will say to you and some things that I won’t. And quite possibly the most important things will be the ones that I withhold.’

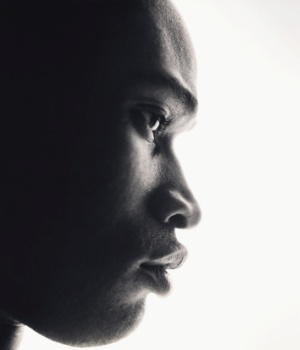

Dionne Brand

The word of the day, at least in America, is ‘post-racial’. That seems unduly optimistic – especially at this moment as I sit to write this text and the embers of a terrible fire, literal and figurative, still burns and radiates its heat in Ferguson, Missouri; even while a caller on NPR says “Mike Brown may not have been armed, but he is six feet tall and over 200 pounds — his body was the weapon he used.” Even while I read over the report from Officer Darren Wilson and see him recount the tragedy in these words: “The only way I can describe it, it look[ed] like a demon, that’s how angry he looked.”

The black body, as dangerous, as threat, as weapon, as something that needed to be brought down – the black body as demonic, as something which attracts to itself the inhuman pronoun– IT –.

And despite all this, there are those who will say, enough of all that. Aren’t we over it. Race is so last year – so last century, even. Can’t we just sing, Kumbayaa and move on? The only race we belong to is the human race.

To be fair, that isn’t just a utopian ideal. Biologists would agree. Race is not a scientific fact – rather, it is a fact of sociology, it is an assignment given to us by the societies in which we find ourselves. I myself, wasn’t really black until 7 years ago – which isn’t to say I wasn’t aware of the colour of my skin, or of the terrible history that brought people like me from Africa to the West Indies. But I lived in Jamaica and, most profoundly, I was simply a person. If someone were to describe me in Jamaica they might say – Kei, oh, he is about that tall, and that kind of build, with that kind of hair, and he talks in this kind of way, rising on the end of his consonants – but no one would have thought to say, oh – and he’s black. My white friends in Jamaica didn’t have that luxury. If you asked someone on the island to describe them they would have said, oh – don’t you know him – he is the white boy? Or she is the Indian girl. Some of my friends knew what it meant to be racialized before I did.

But then in 2008 I moved to Scotland, and for ease of reference, for the ease of description, I became black.

I understood then what it meant to be racialized, and what it meant to live in a world different from others around me, what it meant to have careless things said to me almost every day – not always malicious things though sometimes they were, and almost never consciously racist things, though sometimes they were – but simply careless things. I understood what it meant to live in a body that made people assume all kinds of things – about the kind of family I grew up in, the kind of life I lived, and even the kinds of things I must necessarily believe. And in my head, the big things – the most important things – they began to turn over and over, and sometimes I even dreamed them. I feel them and I dream them but they have almost never been said. In Jamaica, Rastafarians sing: ‘I could go on and on, the full has never been told’.

Recently, I wrote this thing that I probably shouldn’t have. You can be the judge. It was just a few months back. Ebola and the panic around it had reached an all-time high. In the Caribbean, another disease – less fatal but more pandemic – was also rising. So I wrote this opinion piece in the newspaper about diseases that spread in developing countries and how we should not only fear these deadly infections but also the infectious stigma and prejudices that so easily enter our conversations.

I tried to be funny and non-threatening and self-deprecating the way so many women learn to be when they take on big subjects like patriarchy, or the way that so many black people learn to be when they take on big topics like prejudice and racism. In the end, the newspaper said it was absolutely fine, this thing that I had written, but it was also short by 200 words or so. Could I please add a little more – just another paragraph maybe. I was against a deadline and so without much thought I added this thing that had happened to me the day before. It seemed incredibly relevant. It was a small incident, but also, it was a Big Thing, and I forgot – I forgot that I couldn’t just say it like that.

Big Things – the Important Things – they have to be framed carefully. You have to prepare people for them. So this Big Thing was actually just a stupid thing a stranger had said to me. The stranger, whoever he is, probably wanted to appear clever and flamboyantly rude but he probably knew that even if he said the stupid thing which he said and got his laugh out of it, that there was nothing I could do. He had seen me, a black man in South London, and he asked me directly, ‘Hey mate, do you have Ebola?’ It didn’t matter that I wasn’t from Sierra Leone or Liberia and had never been there, or that there were no cases of Ebola in the UK. What mattered was that I was black and that I looked like someone who might be carrying some extravagant third world disease.

There was a flood of responses to this opinion piece, a torrent of cynicism that took me by surprise. They asked: why would you make up a story like that? Clearly, that didn’t happen. Things like that don’t happen here – not in London – so why would you lie!? I thought again about how we live together in this world, but how some of us live in it differently – how I sometimes experience things that I cannot always tell you about.

On the Sunday when that piece was published, I went to my Aunt and Uncle’s house. They’ve lived here for over forty years. The newspapers were spread out on the dining table. My Uncle greeted me with, ‘Oh – there you are. I read your piece. It was good – except for that story that you made up.’

I asked him, ‘Why not?’ and he said something that maybe only someone of his generation could say without irony and with no sense of shame.

He said, ‘Because white people don’t want to read things like that.’

I was angry of course – angry at his initial lack of belief, angry that he had been born in a world where he had learnt this habit of constantly editing himself, censoring himself, making himself acceptable, and I was especially angry because I too had been born to such a world, and maybe even my god-children 2 and 4 years old, had been born to such a world. I was angry, because as much as I disagreed with him, I suspected he was right.

Do you really want to know something I have never talked about? Well it’s simply that: that there is so much I have never talked about.

It is March, and I am in New Zealand being interviewed on stage. It goes well. The next day I am walking through the streets of Wellington – Wellington which turns out to be a smaller city than I had imagined, but the harbour, as big as a sea but so much bluer and cleaner than Kingston’s harbour, gives this whole place a special feeling. A man I do not recognize runs up to me and clasps my hands.

‘You’re Kei Miller,’ he says. ‘I heard you yesterday. I was sitting in the audience. It was a great session.’

I thanked him, but he wasn’t finished with his effusion. He continued: ‘And it was so remarkable, the shocking disparity between your eloquence and your physical appearance.’

And do you know what I said to that?

I stuttered, but the only words that came out of my mouth, cautious, hesitant, were – ‘oh, yes, thanks’. There have been nights since then that I have woken up and thought about the fact that I responded to this man with thanks. But often it is like that. The Big Things, the Important Things, they stall on our tongues and they never come out. We find ourselves strangely worried about hurting the feelings of those who hurt our own. We don’t want to make things awkward or uncomfortable. At a point in time, black bodies all learn the lesson that whenever racist things are said to us, they were not really meant. Of course, of course they were not meant. There was no ill intention. Or the person was going through a rough moment, or they were drunk. We should never, ever confront the person, because that might make them uncomfortable, or hurt their feelings. Their hurt feelings are more important than our own. The job of the black body is always to absorb.

Look…it’s not that I don’t want to say the Most Important Things – but that it takes so much bloody effort. We have to watch our tone; we have to create an ‘out’ so people don’t feel personally accused; we can’t ever seem too aggressive or angry or accusative; we have to tell our stories in the most circuitous ways. We can never just tell them straight.

A black writer has to consider how his or her words might fall on white ears, because if those ears decide to close or to tune out it might mean one less sale, and the economy of publishing subtly tells us that some ears are more important than others. And there! Just there – do you see how that happened? How sometimes a Big Thing just slips out when you’re not careful.

That I am a black man speaking now to a largely white audience is a major construction of the present text. Blackness and ‘whiteness’ structure and mediate our interchanges – they mediate them so that there are some things that I have said to you and some things that I haven’t. And quite possibly the most important things are still the ones that I have withheld.

You sir, are simply awesome. I love, admire and respect you. Your writing is enviable. And that way you talk – like my also amazing late auntie Hortense Ellis.